The Race for the Áras Read online

Contents

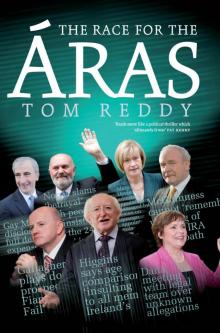

Cover

Title page

Chapter 1: The race

Chapter 2: The runners

Chapter 3: Pulled up

Chapter 4: The ringer?

Chapter 5: The parade ring

Chapter 6: The people’s favourite

Chapter 7: The tipsters

Chapter 8: The presidential endorsement

Chapter 9: Non-declared at 25 to 1

Chapter 10: Late entrants

Chapter 11: The enclosure

Chapter 12: The off

Chapter 13: Front runner

Chapter 14: Stewards’ inquiry

Chapter 15: The going

Chapter 16: Winner all right

Appendix: Presidential election count, 2011

Images

Acknowledgements

Copyright

About the Author

About Gill & Macmillan

Chapter 1

THE RACE

In the dead heat of Beirut a team of armed Irish soldiers, wearing the sky-blue berets of the United Nations, waited in a jeep outside the international airport for the courier to arrive from Dublin.

Dressed anonymously in civilian clothing, the courier had flown on connecting commercial flights from the Defence Forces Human Resources Department in Newbridge, Co. Kildare, to the Middle East carrying a bundle of five hundred envelopes, each containing a ballot paper.

The courier had kept the precious parcel of papers in carry-on hand luggage, rather than risk putting them in the hold, where they might be sent on to the wrong destination. From Beirut his escort drove him south over dusty roads to the UNIFIL base in Tibnin, Lebanon, where 450 Irish soldiers were on peacekeeping duties, each one empowered to vote for the next supreme commander of the Defence Forces.

The same courier would visit other Irish missions in the region to deliver voting papers and then collect the sealed ballots. At the same time another eight couriers from Defence Forces Headquarters would travel to other far-flung corners of the globe to ensure that the constitutional right of Irish soldiers to vote would be fulfilled.

The other places the couriers travelled to included Kosovo, Uganda, Western Sahara, Côte d’Ivoire and Democratic Republic of Congo. An armed escort also met the courier when he arrived in Afghanistan, another extremely dangerous overseas post.

In September each year members of the Defence Forces must fill out form RFC so that they can receive a postal vote. As the presidential election loomed, the Defence Forces Human Resources Office liaised with each constituency returning officer to collect a postal vote for every soldier serving overseas. These ballot papers were forwarded to the Human Resources Office in Mobhí Road in Glasnevin, where they were sorted by country and allocated to the different couriers.

Because there is no postal service in some of the countries in which Irish soldiers serve with the United Nations, the Department of Defence sought quotes from two transnational courier services for delivering and collecting ballots from around the world. However, neither company could provide a service in Bihanga in Uganda or in Democratic Republic of Congo unless they sent individual couriers. However, the quote for a commercial courier was far in excess of the cost of sending a team of their own Defence Forces couriers from Ireland.

While the country would vote on 27 October, soldiers on overseas missions, to accommodate airline schedules, voted as soon as they were given their ballot paper.

In Lebanon, the largest overseas Irish mission, the courier based himself in the village of Tibnin, where he distributed more than four hundred postal votes. He then collected the marked ballot papers and flew back to Dublin, having built time in to his schedule for flight delays or other unforeseen circumstances.

The couriers kept their bundles of votes on their laps during each flight. Once through Customs they would post the hundreds of votes in the postbox in Terminal 1, or in the main concourse in Terminal 2, entrusting the votes that had travelled thousands of miles into the care of An Post, which would deliver them to returning officers in every constituency in the country.

In the blizzard of official forms issued by the state every year, the innocuously named PR1 is very exclusive and, were it available, would be a collector’s item. It is used to record the results of the count in each constituency for the presidential election, and each one is issued exclusively to the local returning officers in each of the forty-three constituencies. It is designed to ensure authenticity in recording and reporting the official result from every presidential poll taken throughout the country.

The officials who conduct the counts would enter the poll figures on form PR1, and the contents would be verified by the local returning officer, who, once satisfied, then signed the form.

For the first count in 2011 some forms would be faxed, and for the first time the others would be scanned and emailed to the national count centre, established in the Old Printing Works in the Lower Yard of Dublin Castle.

Four fax machines, a bank of land lines and computers set up with spreadsheets were at the nerve centre of the national count. As explained by Barry Ryan of the Office of the Presidential Returning Officer, to ensure accuracy, and to counter any possible security breach, the results, faxed or emailed, were confirmed with the local returning officers by phone.

The count centre was in a room beside the press and reception centre, which was draped tastefully in curtains with four banks of work stations. There were a number of mini-stages for television cameras and press photographers. Around the windowless room, the size of half a football pitch, plasma screens hung from the walls displaying results of every count as they arrived from each constituency.

The 2011 election was only the second time that votes would be counted in the constituency in which they were cast and then collated at a national count centre. The new system was established in 1997, but there was no poll in 2004, as the incumbent, Mary McAleese, was returned without contest.

At the previous presidential election, in 1990, ballot boxes filled with the country’s votes were driven to the RDS show hall in Ballsbridge, which was established as the national count centre, with corrals for each constituency count centre, sorting boxes, storage areas, central stages and a press centre. But in 1993 legislation was introduced that decentralised the counting, capitalising on the long experience and the expertise of each constituency in conducting organised counts for local and national elections.

The polling of 27 October 2011 had its own logistical characteristics. The presidential election—the contest for the post of guardian of the Constitution of Ireland—would be voted on at the same time as two proposed constitutional amendments, one relating to providing extra powers of investigation to politicians, the other to allowing judges’ pay to be regulated in line with other public officials. In the Dublin West constituency a by-election would also be held to fill the seat of the late Brian Lenihan (junior) of Fianna Fáil.

The count centres throughout the country would open at 9 a.m. The first task of the teams of approximately forty counters supervised by local returning officers in each constituency was to sort the three different papers: the two referendums for constitutional amendments (blue for the Oireachtas inquiries referendum and green for the judges’ pay referendum) and the white paper for the presidential poll, which had colour photographs of each of the seven candidates.

For tallymen—the dedicated party supporters who would volunteer a day and a night, and a promise for the following days if needed—this initial sorting process was slow, something that allowed them extra time to observe and estimate first and sometimes second preferences. In a general election a skilled tallyman, particularly in provincial areas, would almost be able to identify

each vote as it was turned out onto the table. That level of detail—necessary in a general election for political parties to be able to identify weak and strong areas, turned votes and new votes—was unnecessary in a presidential election. This was a straightforward race, so only number 1s would be important if there was a landslide. However, preferences would be vital in deciding the outcome if candidates were grouping together with similar poll figures.

The presidential poll is the simplest and fastest to count of all elections. More than 3.1 million people were eligible to vote in the 2011 presidential election. The ballot papers would be sorted according to first preferences and the result sent by the local returning officer on form PR1 to the national count centre.

The presidential returning officer compiles all the figures and calculates the quota a candidate must reach to be elected. With only one position to fill, the quota is 50 per cent of the valid votes plus one. If a candidate receives a number of votes equal to or greater than the quota, they will be declared elected. However, if no candidate reaches the quota on the first count, the presidential returning officer will direct the local returning officers to eliminate the candidate with the lowest number of national first-preference votes. Those ballot papers are then scrutinised and the next available preferences on those papers are allocated to the remaining candidates, and this is followed by a second count.

If at the end of any count the sum of the votes of two or more of the lowest candidates is less than those of the next-highest continuing candidate, the returning officer must exclude those two or more candidates. However, this provision takes effect only if the multiple exclusion does not affect a candidate’s chances of achieving more than a quarter of the quota, which would allow them to recoup their election expenses.

The Electoral (Amendment) Act (2011) limits expenditure by a candidate for the presidential election to €750,000. However, the clock on election expenditure starts ticking only after the Minister for the Environment makes the Presidential Election Order. Candidates who enter the field early are free to expend any sums of money or assets they have or have garnered before the minister’s order is put into effect.

An election agent appointed by the candidate, or the candidate themselves, must account for all spending on the campaign and must provide a statement of those expenses to the Standards in Public Office Commission. A copy of this statement is then laid before each house of the Oireachtas, formally putting the information in the public domain.

The same legislation allows for candidates who receive more than a quarter of the quota to apply for reimbursement of their expenses of up to €200,000, funded by the taxpayer.

While it is unlikely that all the preferences of an eliminated candidate will transfer to one candidate, the presidential returning officer will always consider the possibility that a candidate might reach (or exceed) a quarter of the quota. As explained by Barry Ryan, if there is a possibility that a candidate might qualify to receive campaign expenses, they may well merit a separate count rather than be included in a block elimination.

Candidates are also entitled to be represented at each count centre—a real possibility for a political party nominee but less likely for an independent candidate without a national organisation. These agents are also empowered to ask for a recount of the ballot papers in their local count centre. At the national level a candidate or their agent can ask for a national recount. However, they may seek this only once during the counting process.

A further appeal, to dispute the result of the election, is available by way of petition to the High Court, presented by the Director of Public Prosecutions on behalf of a candidate or an election agent. The High Court, having considered the case, could order that the votes be recounted, or the poll taken again, in any constituency, or could declare the election void. In such a case a new election would have to be held. The High Court’s decision is final, subject only to appeal to the Supreme Court on a question of law.

Once elected to office, the President has very few powers. Though some are significant, they may be used only rarely.

The office of President was established by the Constitution of Ireland in 1937. The President takes precedence over all other persons in the state, and exercises powers and functions conferred by the Constitution and by law.

The main function of the President is to scrutinise legislation. After consultation with the Council of State, the President may decide to refer a bill that has been passed by both houses of the Oireachtas to the Supreme Court for a decision on its constitutionality. However, if a majority of the Seanad, and at least a third of the Dáil, form a petition, the President, following consultation with the Council of State, may decline to sign a bill until the will of the people has been ascertained by referendum or general election.

Other tasks that fall to the President, rarely but significantly, are the appointment of the Taoiseach on the nomination of the Dáil, the appointment of the other members of the Government on the nomination of the Taoiseach with the previous approval of the Dáil, and the acceptance of the resignation or termination of the appointment of a member of the Government on the advice of the Taoiseach.

The President can summon or dissolve the Dáil on the advice of the Taoiseach but may refuse to dissolve it on the advice of a Taoiseach who has ceased to retain the support of a majority in the Dáil. In addition, the President can exercise the right of pardon, has the power to remit punishment imposed by a court of criminal jurisdiction and, following consultation with the Council of State, can communicate with the houses of the Oireachtas on a matter of national or public importance or address a message to the people.

While the President holds the highest office in the land, and is not answerable to either house of the Oireachtas or to any court, a safeguard is built in to the Constitution that provides a procedure for impeaching the President for stated misbehaviour.

The two previous holders of the office, Mary Robinson and Mary McAleese, stretched the influence and significance of the office by publicly associating it with their presidential themes. Mary Robinson had dramatically drawn to the attention of the world the plight of people in famine-ravaged Somalia and later to the victims of the Rwandan genocide. The work of Mary McAleese and that of her husband, Martin, in fostering North-South relations during her tenure reflected her original campaign theme of building bridges.

Governments have had every day of their tenure recorded and analysed by the media as they enjoyed or coped with controversy. Presidents, as non-political entities, have for the most part avoided controversy; but when controversy hit, it hit hard, at the office and the office-holder. The television presenter Pat Kenny would later say that media scrutiny of candidates was justified, as it would draw attention to, inform about or provide an insight into how a presidential candidate might react in the face of intense political pressure.

Controversies, some of national import, marked some of the occupants of the Áras. Dr Douglas Hyde, the country’s first President and the first poet in the Park, was expelled from the GAA for attending a rugby match in his official capacity. His funeral service in St Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin, was not attended by members of the coalition Government, because of the edict of the Archbishop of Dublin, John Charles McQuaid, forbidding any Catholic attendance at a Protestant service. Instead, ministers sat sanctimoniously and ostentatiously in their cars outside the cathedral as his soul was commended to God.

The mild-mannered Erskine Childers contested the 1973 election and won the race despite the Fine Gael candidate being the favourite, having been a keen contender in the previous election against Éamon de Valera. However, there was tension between his office and the Government led by Liam Cosgrave after they rejected his proposal to establish a think-tank in the Áras—a proposal that was probably before its time.

After the untimely death in office of Childers, Fianna Fáil proposed Cearbhall Ó Dálaigh, a former Chief Justice, as its candidate. There was no opposition to his candidacy

. The news editor of the Irish Independent, Don Lavery, recalled what was supposed to be a routine ‘marking’ or ‘job’ for him as a young reporter on the Westmeath Examiner at Columb Barracks, Mullingar, on Monday 18 October 1976. Loyalist bombs had caused mass murder in Dublin and Monaghan, and the IRA had murdered the British ambassador and a garda in a booby-trap bomb. The Government responded by proposing to give the Gardaí more powers in an Emergency Powers Bill. President Ó Dálaigh referred the proposed law to the Supreme Court, angering some members of the Government. The Minister for Defence, Paddy Donegan, who was formally opening a canteen in Columb Barracks, didn’t deliver the speech he had brought with him.

He stood up, and threw it down on the table in front of me. Looking at me, he said: ‘I’ll give you some news for the press.’

I took down his remarks in shorthand as he criticised Ó Dálaigh for sending the bill to the Supreme Court. Asking why he had not sent other aspects of anti-IRA laws to the court, Donegan said: ‘In my opinion he is a thundering disgrace.’

A friend, an Army officer, kicked me on the shin in case I had missed the importance of the remark. I hadn’t. Donegan had insulted the Supreme Commander of the Defence Forces in a room full of commissioned officers. The words used were ‘thundering disgrace’—not ‘fing disgrace’ or any other phrase. Donegan was not drunk. He had been quite definite in what he wanted to say.

Lavery’s report caused a political storm. Ó Dálaigh demanded the minister’s resignation. Donegan offered it, but the Taoiseach, Liam Cosgrave, refused to accept it, so Ó Dálaigh resigned, becoming the only President to resign in office. The bill was subsequently found to be constitutional.

Paddy Hillery from Co. Clare, vice-president of the European Commission and a former Fianna Fáil TD and firebrand with a quiet humour, was pressured by the party leader, Jack Lynch, into accepting the role of President without a contest. He accepted; on taking up a second term he remarked that it was his reward for ‘good behaviour’ and effectually ‘doubled’ his sentence in the Park. It was a position he had never wanted, but his steely determination and low-key approach reasserted the authority of the office.

The Race for the Áras

The Race for the Áras